9. Things Unseen

In the years following Lynn’s appearance on Jeopardy!, she would occasionally tell me things she’d seen and experienced as a contestant, things that go unseen by the rest of us mere mortals. Usually, these moments of revelation came at the least expected times, like floating in a warm summer sea or, as you’ll read below, cleaning an empty house.

Lynn had her reasons for keeping her experiences on Jeopardy! close to her. Abused children are survivors. They learn skills that stay with them and remain unseen by those of us who are lucky enough to grow up in non-abusive families. For a victim, things that are important to you, that become a part of you, need to be hidden from everyone. Memories are what you own, and they can be stolen away and used against you, just as everything else has been stolen away in your life until there is little left. To survive, a victim wraps the only thing they truly own—their memories— tightly around the core of their being. Like a well-trained soldier, survival techniques become second nature. She had survived an unseen war, and I knew better than to ask any soldier about their war experiences, because, by unseen fate, I have no frame of reference that would allow me to fully understand. The fact that Lynn told me about some of her Jeopardy! memories was an outward sign of her trust in me, of her love for me.

Knowing some of the things unseen gives us a different perspective.

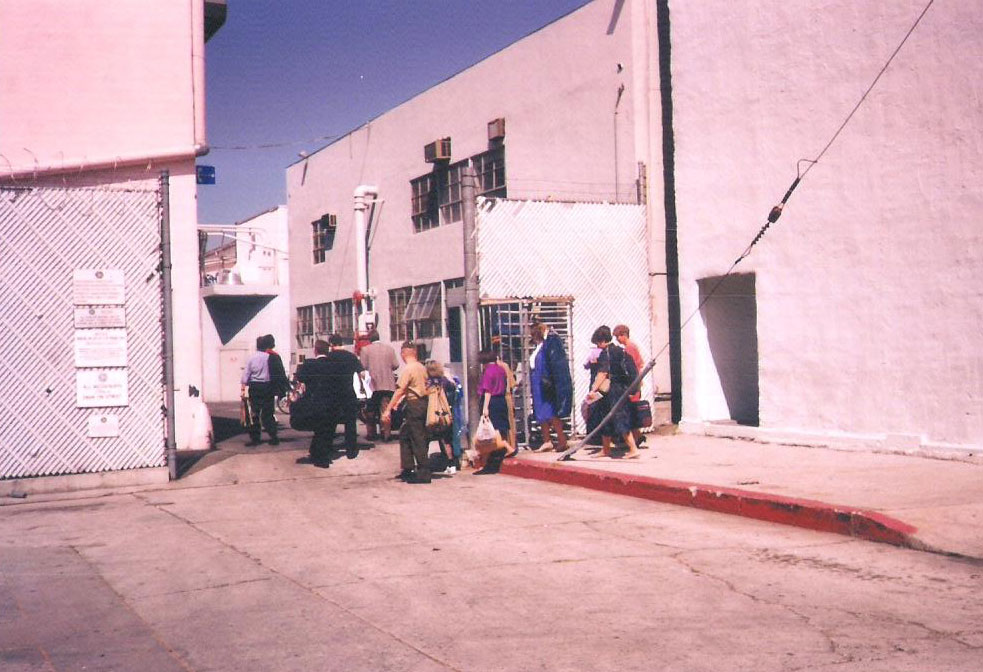

At 10:30 AM on Tuesday, Glen, an assistant contestant coordinator, came out into the back alley of the Hollywood Center Studios, Stage 1, to welcome Lynn and the other 12 contestants to Jeopardy!. This wasn’t at all like what Lynn had imagined. She imagined a hotel-like lobby area, where brave contestants are led to a presentation center for orientation, with movie theater carpet, comfortable seats, and hallways decorated with framed art and historic photos from the show. This was a back alley— a hot back alley outside the studio, with no chairs and a bright blue ceiling of infinite height.

Lynn told me that before they finally went into the studio, Glenn explained that from this moment on, they would need to be escorted by a contestant coordinator or someone from Standards and Practices until they left the studio that evening. “No wandering off to explore. You can talk with the other contestants, but no talking to the crew. It’s important; you don’t want to get disqualified after getting this far, right?” And with that, from far down the alley on the other side of the studio gate, I watched the jeopardy of contestants, like a single-file gaggle of goslings, follow Glenn through a tall gate with a turnstile of the sort you’d find at a sports stadium. I was so proud of Lynn; I could never have gotten a ticket to enter that arena.

A jeopardy of contestants.

In 1994, we were moving into our second house in Wilmington, DE. We were anxious to move out of the college town where we’d lived for the past 15 years and into a community of fellow diurnal creatures. A few days before we moved into our still-empty house, we were cleaning upstairs. Lynn took a break from sweeping and watched as I struggled to disassemble an old tubular wardrobe rack that had been left behind by the previous owners. It was too big to get down the stairs fully assembled and it was proving to be hard to get apart. I guess that’s why it was left for the new owners. “That’s like the clothes rack they had at Jeopardy!,” Lynn said.

There were no dressing rooms, Lynn told me, at least not for the contestants. Glen brought them into what was essentially a not-so-big break room. There was an empty wardrobe rack along one wall where they could all hang their clothes (three days’ worth were required). One long Formica table was in the middle of the room with kitchen table chairs, complete with vinyl seat covers, scattered around the table and placed along the walls. Lynn said it reminded her of the break room in the Townsends, Inc. chicken processing plant in Sussex County, Delaware, that she’d once toured on a school trip. “I guess I know what happens to surveillance chickens when they retire.”

That was funny, of course, and I immediately knew what she meant. But something will go unseen if we don’t stop and think about Lynn’s connections and what they mean. It was a happy moment, cleaning out our new house, getting it ready so we could move in. The wardrobe rack reminded Lynn of another happy time. As she was telling me about the Jeopardy! break room, she remembered the chicken processing plant, which led back to the surveillance chickens at the La Brea Tar Pits. Lynn’s life had taught her that joy is often balanced by sadness, danger, or even tragedy. The surveillance chickens live a happy, well-fed life—unless they develop encephalitis. And even if they don’t, the possibility of a chicken processing plant looms in their future. For people and chickens, the future remains unseen. The difference is people know there is a future, whereas chickens live entirely within a moment in time. I think most people try to live their own lives that way, enjoying the moment, not always thinking about what’s unseen in the next moment. I’m more like the chickens: happy to live out my life in ignorant bliss. Lynn had learned that every moment has consequences. Lynn needed to be prepared for those unknowns, even if that meant tempering the joy, for her life had taught her that blindly living in the moment is often dangerous.

As I struggled with the wardrobe rack, Lynn continued to tell me about Jeopardy!. First, Glen outlined the day’s schedule. Filming starts at 2:00 PM. They film three shows, with a fifteen-minute break between shows for Alex and the returning champion to change clothes. Between games three and four, there’s a short break for lunch which is set up on the sound stage next door. No one can leave the building until they’re done filming all five episodes. Filming resumes at 5:00 PM with a new studio audience and continues until they have five shows “in the can,” usually between 6:30 and 7:00 PM.

Next, Glen explains that they film live. They “start tape” at the beginning of each episode, and it rolls until the end. When they come to a commercial, the tape keeps rolling, and the break lasts precisely as long as the commercials, which are plugged in later in post-production. The only time they “stop tape” is before Final Jeopardy. The clue crew will come out with paper and a calculator so you can accurately figure out your wager. You can take as much time as you need for this, which is why they stop the taping. The crew will ask you if you’re sure about your wager, and they’ll tell you to write the beginning of the Final Jeopardy question: “What is . . .” or “Who is . . .” When everyone’s ready, the “The Dress” claps them back in.

Glenn told them if Alex makes a mistake—but quickly added Alex doesn’t make mistakes—the game doesn’t stop. He said read the clue even if Alex doesn’t finish reading it. Signal in when you see the lights around the board go on (see below), and answer just as if nothing went wrong. It’s why they keep the tape rolling: Alex rereads the clues he’s not happy with during the commercial break. They dub Alex’s correction back in during post-production. And, if you dispute an answer, you’re not supposed to say anything until the commercial break. Then, the judges will research your challenge and adjust the scores during the break if needed. They don’t stop tape. If they have to stop tape, well, Lynn said Glenn told them, “It’s complicated. People get grumpy. We don’t stop tape!”

Then, Lynn said they all filed down to the floor of the ice-cold set. Each prospective contestant got to try out the signaling device and practice writing with the light pen. Lynn said it’s tricky because there’s a slight delay as you write: it takes half a second for the display to catch up to what you’re writing. The crew also noted which vertically challenged players needed boxes to stand on when behind their podium. Apparently, the cameramen hate to bob the camera up and down as they pan from player to player, so they try to make everyone the same height. Lynn’s box was black, the top of which had been scuffed to the point of exposing bare wood.

Another unseen thing is lights around the edges of the main board of clues. The signaling device isn’t activated until Alex is done reading the entire clue. The lights around the board, which aren’t visible to the T.V. viewing audience, come on when the signaling devices become active. If you try to signal in before the lights come on, you get locked out from signaling in again for a tenth of a second. The lights are there so that if Alex messes up reading a clue, one of the judges will activate the lights so the contestants can signal in and the game can continue without having to stop tape. Alex is never on camera when he’s reading the clue, so it’s just a matter of dubbing in new audio.

In late October 1992, we were grocery shopping at the Acme in Newark. Lynn filmed the shows in August, but they weren’t aired until mid-October. The checker recognized Lynn. “Hey! You’re the Jeopardy! champion from Newark, aren’t you?!” she said, a little loudly. “I seen ya on the news!” There was a sudden twenty-foot circle of silence around Lynn as everyone stopped to look, broken just as suddenly by people clapping. “Wow! What was Alex like?” the checker asked. That was the second most asked question Lynn would get when people found out she’d been on Jeopardy!, the first being, “How much did you win?” This was the first time Lynn had been recognized in public, and it caught her—and me—completely off guard. She was embarrassed but at the same time exhilarated. As people closed in to hear her, Lynn explained to the checker that the Alex you see on T.V. is as much of him as she sees. The only time you get to talk to him is when he’s on stage, ‘cause he knows all the answers. Then, answering distant queries, she added, “$29,200...a trip to Montreal...a year’s supply of Klondike Bars and Dentu-Grip.” Thinking back now, I remember the expressions on peoples’ faces. Because of Lynn, smiling people left the store with a story to tell, a happy story. “I met a Jeopardy! champion!”

Driving home, Lynn told me about seeing the president of the University of Delaware earlier in the day at work. She worked in the same building as the president; his office is in what the worker bees call “The Mahogany Corner.” She often passed him in the halls of the building, but she’d always been one of the unseen—until Jeopardy!. He and the Provost were taking a group of IT executives to lunch at the faculty dining hall, a place full of flowers but never any bees. As the group approached Lynn, walking in the other direction to her lonely, frugal lunch at The Malt Shop downtown, he suddenly said, “And here’s our Jeopardy! champion, Mrs. Loper. She’s in admissions. You may have just seen her on TV. Good afternoon, Mrs. Loper; so nice to see you.”

“It was weird,” Lynn said, as we carried in the groceries. I mentioned the smiling faces that had gone unseen by her at the grocery store. “It just doesn’t seem right. It’s still just me in here.”

Do things unseen change to become suddenly seen, or does something change in the observers so that they suddenly see differently?

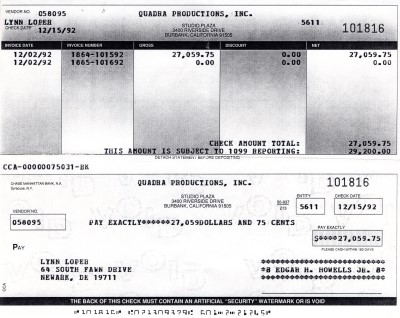

Remember the all-caps warning message about there being no guarantee that you’d actually appear on the show? There’s more, something unseen, or at least unconsidered. If the show you were on doesn’t air, you don’t get any of the prize money or even the lovely parting gifts. No Dentu-Grip. We didn’t think much of it at the time; why wouldn’t it air? Why? There was a presidential campaign going on in 1992: Clinton, Bush, and Perot. Lynn’s first game was supposed to air on Thursday, October 15th, at 7:00 PM Eastern Time. When the debate schedule was first announced in early October, the debate (the second of three) was slated to start at 8:00 PM on October 15th, with network coverage beginning at 7:00 PM with a “pregame” show. Jeopardy! would be preempted. Lynn’s show would never air. Lynn tried to act as though it didn’t matter. Being able to qualify for the show had always been the only goal. The fact that she got to film three episodes was rewarding enough. Her eyes said differently as I went to hug her.

Things unseen move beyond our knowing and understanding.

One candidate had a scheduling problem, so the debate was moved to 9:00 PM, and Jeopardy! aired at its usual time on October 15th, 1992. So, when Lynn returned from the Acme a sudden celebrity that afternoon in late October, we were able to set our groceries down on the table Lynn had bought at Ikea, knowing that an as-yet unseen check from Hollywood would be coming in December.

Email: Tom Loper

Email: Tom Loper